Shemza was born in Simla, now Shimla, and went to school in Lahore, then India, now Pakistan. It would be trite to try and render the dislocation of such circumstances. Perhaps you can do the thinking better than me. The context is that he graduated in 1947, a year in which several of his relatives died in the Hindu – Muslim – Sikh violence that was ablaze in northern India.

In the same year, he set up a commercial design studio. He was a multifaceted man; designer, artist, writer (four novels in Urdu, multiple radio plays, much poetry). On top of which he taught widely.

Renowned in Pakistan, he came to London in 1956 to study at the Slade, and in many ways England made a great life small. His adopted homeland of Pakistan was a deeply complicated place, but in Europe he found a post-war Britain which cared little for non-European cultures. After a few years in London he moved to Stafford, where he remained adrift of the art establishment. In Pakistan his visual and literary eloquence had been celebrated. Within a few years in England he was art teacher in a school north of Walsall.

Looking back at his days at the Slade, he recalled his thoughts on a lecture by Gombrich on Islamic art:

‘As the students came out, I looked at all their faces; they seemed so contented and self-satisfied. I went home and looked again in the mirror. This time I couldn’t find any familiar face at all, neither the beginner at the Slade nor the ‘celebrated artist’… All evening I destroyed paintings, drawings, everything that could be called art… All day restlessness sent me from place to place, until I found myself in the Egyptian Section of the British Museum. For the first time I felt really at home.’

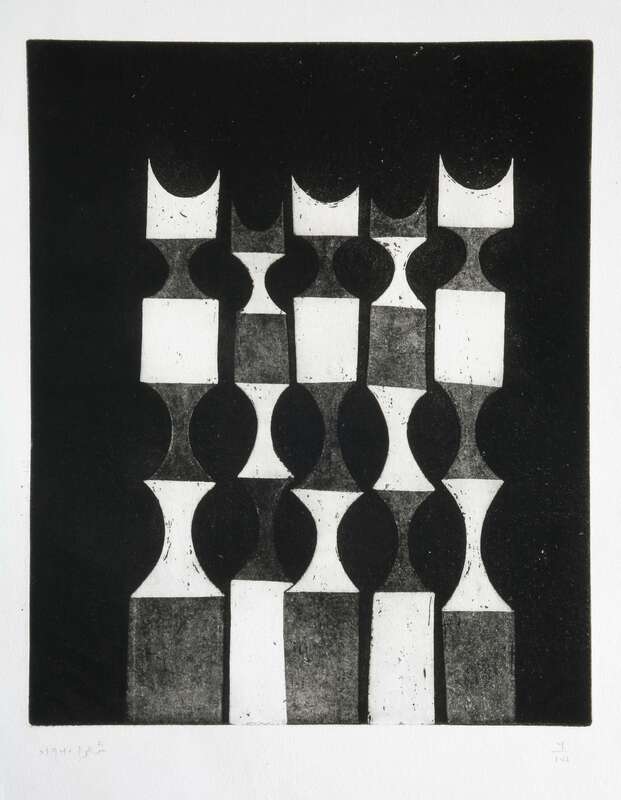

Five Standing Forms, 1960, courtesy of the artist’s estate

His work is many things. It is calligraphic, full of grace. It slips from the three-dimensional to the two almost without you knowing, quietly grounding things to flat and linear forms. There seems to be some bind that you can’t identify, a quiet magic, a longing for another place, as if there are always other circles and squares, or things not there in front of you. Perhaps I’m projecting.

So he was far more of a pioneer than this (admittedly very fine) painting in the Tate might tell you. He eked out a life during partition, he went to Europe, he married a woman called Mary Taylor, and ended up in Stafford. He is an offstage name alongside the known giants of Mondrian and Klee. But his arena was also the surface – the oddity of all paintings – where his work is also invested with a mysterious life.

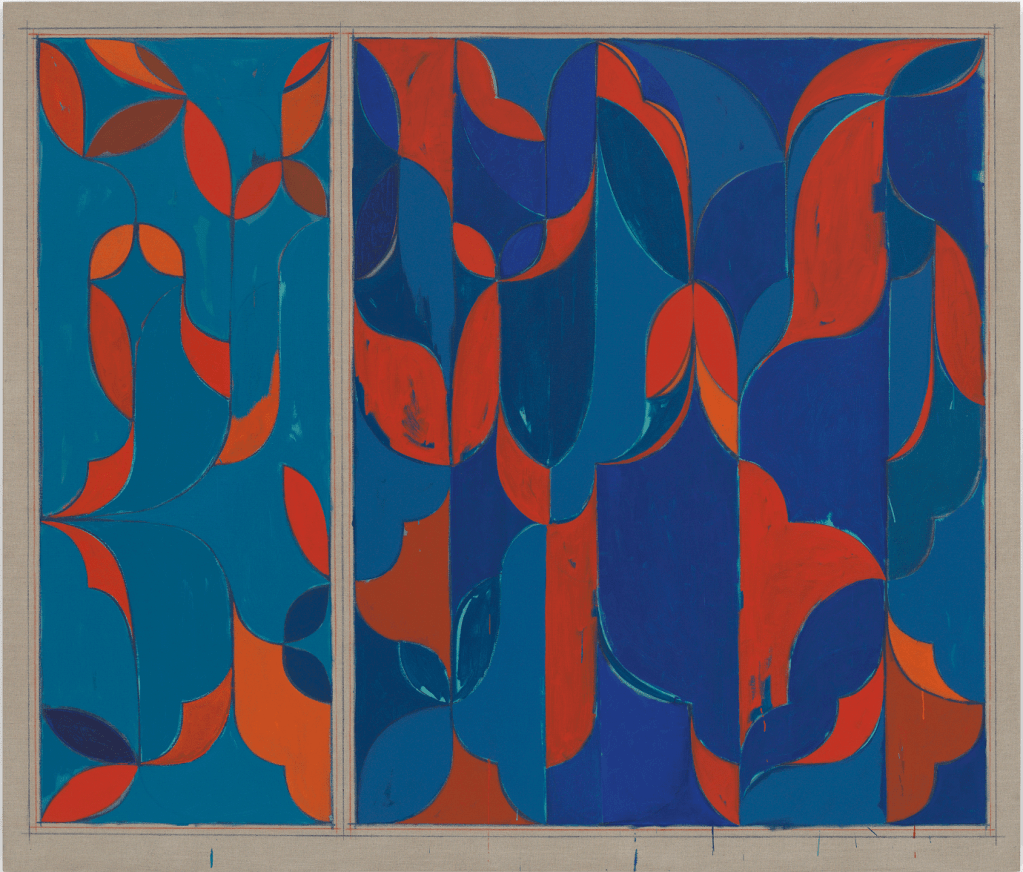

His canvases are like rugs – full of pattern (but not only pattern), and texture despite their fundamental flatness, full of fiction in their ideas, but real and readable. Perhaps I’m imagining it all, but there’s a chance there’s something there – his family had a carpet business.

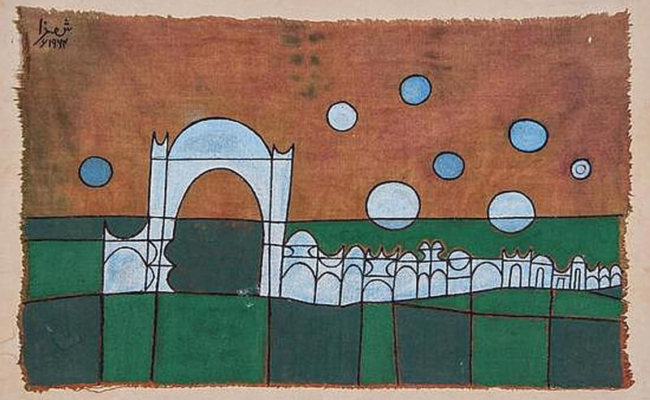

Looking over his work certain themes and motifs recur. The walls and gates of Lahore, the Arabic letter ‘Meem’, the interaction of Islamic and western art forms. Tasveer Shemza (his daughter) has animated these recurrences: “I have the most incredible reminder of my father’s work – a lively piece from the Meem series. I had it on my wedding cake and for my 50th birthday had it made into stained glass for my front door”.

Shemza on a cake, Shemza on a door. I would. And then there’s this, because its so happily post-Shemza, or pro-Shemza; Shemzian?

Leave a comment